Writer Elizabeth Day has received wide acclaim for her four wonderful novels, Paper Scissors Stone, Home Fires, Paradise City and The Party – a favourite in Papier HQ. With March celebrating both World Book Day and International Women's Day, it seemed like the opportune moment to ask Elizabeth to tell us about the female authors who have influenced her own writing.

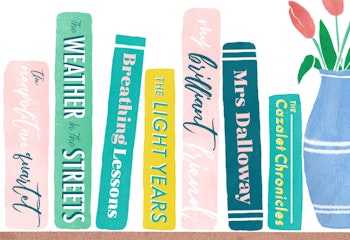

It wasn't until I wrote this piece that I realised the female authors who have most influenced me as a writer had such similar themes and preoccupations. Taken collectively, the novels below span two centuries and three countries, and yet they have more in common than you might expect. Each of the authors is concerned, as am I, with exploring universal themes through the prism of individual experience; a couple of the works explicitly examine the experience of war on the home front, but all of them describe the more intimate battlefields of friendship, family and human intimacy.

Too often, female authors are dismissed for their supposed preoccupation with the "domestic" sphere: when women write about family dynamics, they're accused of a lack of imagination; when Jonathan Franzen does it, he's praised for his state-of-the-nation gravitas. But the distinction is a false one – after all, Anna Karenina was about a family. And as the books below demonstrate, the best writing illuminates big truths no matter how small the canvas.

1. Elena Ferrante, The Neapolitan Quartet

Elena Ferrante writes with such blazing intelligence and indignation about what it means to be a woman that this quartet was, for me, a revelation. The four novels, which start with My Brilliant Friend, chart the course of a best friendship between two women, Lina and Lenu, who grow up in the patriarchal confines of 1950s Naples. The details of their entwined life are minutely observed and rendered: from a shared childhood in an impoverished neighbourhood, through to adulthood with its passionate love affairs, burgeoning careers and complex family struggles. The intensity of the friendship is played out against a backdrop of crime and political corruption. Ferrante's point is that the personal can never really be separated from the political.

Platonic female intimacy is not often explored in great novels, but Ferrante took the archetype of classic literature and applied it to this overlooked area of human experience. Her writing lies beyond stereotypical notions of what it is to be a 'male' or a 'female' writer. It just is. And it's brilliant because of it.

2. Elizabeth Jane Howard, The Cazalet Chronicles

Elizabeth Jane Howard was a huge influence for me – and I was lucky enough to meet her before she died in 2014. The Cazalet Chronicles consist of five novels, spanning two decades in the life of one, sprawling family from the eve of the Second World War. Like Ferrante, Howard's fictional sphere is domestic and yet reveals deeper truths about human nature. Her characters leap from the page like living, breathing people and her acutest insights are reserved for what makes us flawed yet lovable. She is the most amazing story-teller because she makes you care.

When I wrote my debut novel, Scissors Paper Stone, I re-read Howard to see how she did it and appreciated for the first time how brilliant she was at the technical craft of writing. Her shifts between tenses and points-of-view are so smoothly done, you move effortlessly from the thoughts of one character to another. That's very hard to do without it seeming clunky, trust me!

3. Anne Tyler, Breathing Lessons

Anne Tyler is a novelist who has elevated the pitch-perfect observation of everyday detail into an art form. There are moments in her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1988 novel, Breathing Lessons, where her prose is so unassuming, so exact in the placement of each word, that it's easy to let it glide over you like an overheard conversation, failing to realise quite how brilliantly it is executed.

Breathing Lessons tells the story of Maggie Moran and her husband, Ira, who are driving from Baltimore to Pennsylvania, for a funeral. On the journey, the marriage is gradually laid bare. Tyler focuses on the mundane, on the tiny details of ordered lives lived on the brink of disruption, on the tensions between what is said and what is meant. She chooses subtlety over grandeur; she thinks in minuscule rather than capital letters. She is also very funny.

It's criminal, I think, that Tyler has never received the public acclamation she deserves. She is not spoken of in the same breath as those other great chroniclers of the American diaspora, men such as Philip Roth or John Updike. Yet her novels are, in their own measured, empathetic way, equally dazzling.

4. Rosamond Lehmann, The Weather in the Streets

The Weather in the Streets is a modern novel, with quintessentially modern themes, that just so happens to have been written in 1936. The protagonist, Olivia Curtis, is in her 20s, divorced, and about to embark on an affair with a married man. She exists as an observer on the margins – in between classes, marriages and social circles – and what I love about this book is that despite her frequently unlikeable actions, Olivia never once loses our sympathy. This is because of Lehmann's astonishing assurance: she glides from first to third person, often in the space of a single paragraph, so that the reader has the curious experience of being both within Olivia's mind and simultaneously outside it. At points, her prose reads more like poetry. The colliding time-frames, the arresting imagery and the stream-of-consciousness passages are all distinctly modernist in flavour. Yet Lehmann never loses her grip on the plot. She is an adept social satirist and her authorial eye is alive to every single detail and nuance of the dialogue. She's funny in one breath, profound in the next. Like Olivia, she defies easy categorisation.

5. Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway

I hadn't read Mrs Dalloway until a good friend of mine told me that my second novel, Home Fires, reminded her of it. I then picked up a copy and was bowled over by the similarities – not in prose (alas!) but in content. Both Woolf and I were interested in exploring the legacy of post-traumatic stress in First World War veterans. Woolf does so in a breathtaking narrative tour-de-force: like James Joyce's Ulysses, the novel takes place over the course of a single day in 1923.

Mrs Dalloway follows the upper-middle-class London socialite Clarissa Dalloway as she makes last-minute preparations for an evening gathering. Woolf's stream-of-consciousness flashes back and forth to touch on her protagonist's depression and troubled past. Shadowing this story is the tale of Septimus Smith, a veteran suffering from shell-shock. The home front is thus inextricably entwined with the front line, and Woolf explores the dynamics of battles fought in both domestic and global spheres. At its core, the novel asks how to connect in a disjointed world, a preoccupation that fascinates me still.

Elizabeth Day's latest novel, The Party, is out now.